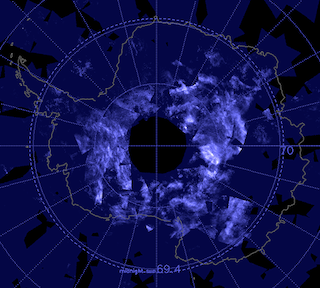

In this Saturday, March 22, 2014 photo provided by the U.S. Navy, sailors aboard the Virginia-class attack submarine USS New Mexico tie mooring lines after the submarine surfaces through the arctic ice at Ice Camp Nautilus, north of Alaska. Cracks in polar sea ice are prompting the Navy to break down the camp that provided support for an exercise involving submarines. (U.S. Navy via AP)

In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that that the Arctic would be ice free in 60 years.

In new projections, that projection has been reduced to as little as six years.

Already the warming trend is having a devastating impact on plants, animals, andn ative seal fishermen, who reportedly sit landlocked and watch huge freighters sail past.

But the melting Arctic ice presents an opportunity for countries that are hoping to capitalize on huge mineral, oil and gas reserves that are now accessible.

Largely they’re cooperating under international agreements. But the Arctic is also where geopolitical tensions are playing out.

Russia has a far greater presence in the Arctic than the United States, and this month, the U.S. put military exercises with Russia on hold in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine. In one exercise the United States aimed virtual torpedoes at a virtual Russian submarine.

Scott Borgerson, a former Coast Guard officer and Arctic expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, joins Here & Now’s Robin Young to discuss the Arctic’s new role in the wake of climate change.

- CFR’s report on the Arctic

- Foreign Affairs: The Coming Arctic Boom

- Wall Street Journal: Cold War Echoes Under the Arctic Ice

Guest

- Scott Borgerson, former Coast Guard officer and Council on Foreign Relations fellow who has been called the United States’ foremost expert on the Arctic. He is on the board of The Terramar Project.

Transcript

ROBIN YOUNG, HOST:

Well, in 2007, the U.N. panel warned that the Arctic would be ice-free in 60 years. In new projections that’s been reduced to as little as six years. Already the warming is having devastating impacts on plants and animals. Native seal fishermen reportedly sit landlocked watching huge freighters sail past. That’s the good news, at least for crews from Arctic border countries scrambling to get access to vast oil, gas and mineral resources opening up.

But of course Russia and the U.S. are Arctic countries as well. So what’s been the effect of the new cool war over Crimea on the melting Arctic, and what exactly is this race to the top of the world? Scott Borgerson is a former Coast Guard officer and Council on Foreign Relations fellow. He’s been called a foremost expert on the Arctic. We’ll link you to his writing at hereandnow.org as he joins us. Welcome, Scott.

SCOTT BORGERSON: Thank you for having me.

YOUNG: You once predicted that a race for resources in the Arctic would inevitably end in conflict. You changed your outlook based on how well you thought nations were working together to deal with this shifting reality there. And now we’re reading of joint military exercises between the U.S. and Russia canceled because of Crimea. The U.S. did hold an exercise this month in which a U.S. crew aimed torpedoes at a virtual Russian submarine.

So what do you say now about how U.S.-Russia relations will impact what’s going on in the Arctic?

BORGERSON: Well, for starters the Arctic is still very much an area of cooperation, not conflict, and this is much to the surprise of those of us watch the region. With the pace of climate change and access to resources, which we might talk about, some thought there might be a race to the Arctic, and I among them. But the last few years have actually shown an extraordinary amount of cooperation, including with Russia, by the way, as Arctic nations and even those beyond the Arctic like China and Korea, Japan, follow the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea and have a number of bilateral and multilateral areas of cooperation.

Crimea and the Ukraine still to be determined how that influences our cooperation with Russia there. But by and large the United States and Russia, as well as the other Arctic countries, have a lot more to benefit from cooperating in the Arctic than competing.

YOUNG: Well, let’s talk about that, but first I want to ask you, you mentioned, is it called UNCLOS, U-N-C-L-O-S, the treaty?

BORGERSON: Yeah, so the Law of the Sea treaty is the overarching legal regime, not just for the Arctic but for all the world’s oceans. It sets the rules for whose resources are where, how jurisdiction and boundary lines are drawn. As the sea ice melts away, the Arctic Ocean is opening and joining the rest of the world’s oceans, and this governance regime, which the U.S. treats as customary international law but has not yet joined, is the binding legal framework for how the Arctic is treated.

YOUNG: Well, you say the U.S. has got a little bit of catching up to do in the Arctic because they haven’t signed this treaty.

BORGERSON: Yeah, this is actually a really big problem for the United States, and it’s embarrassing, frankly. There’s only a handful of coastal nations who have not yet joined the treaty to include Iran, Syria, North Korea. Those are our counterparts here. By not being a formal member to it, there are lots of rights and responsibilities we lose out on like submitting our claim to extended continental shelf under the provisions of the treaty, being able to use other provisions for enacting stricter environmental and shipping standards abroad.

Bipartisan groups support this treaty, and many of us are hopeful that the U.S. Senate will actually see it through.

YOUNG: Well, especially as people are realizing how important this area is. Just tick through some of the resources in the Arctic that people are suddenly paying attention to.

BORGERSON: So the world’s largest nickel mine, the world’s largest zinc mine, many of the world’s largest reserves of coal, precious metals, rare earth elements, and in a great paradox, perhaps the largest amount of undiscovered hydrocarbon resources of oil and gas. In fact, the U.S. Geological Survey estimates that nearly a quarter of the world’s oil and gas left to be discovered are found in the Arctic.

YOUNG: But this is also one of the last pristine areas in the world. What are the questions about – put aside the political questions about who gets this, and right now you say there’s cooperation, what does it do to the area?

BORGERSON: So there’s going to be increased activity, and that’s part of what I write about. We have to operate there responsibly. What should be new standards of shipping that use these routes? How do we safely drill for oil and gas, which has been an issue off of Alaska with the shales project. How do we respond to oil spills in the Arctic?

YOUNG: Well, in fact you write there’s the equivalent of 14 Exxon Valdez disasters every year because of substandard Russian infrastructure. So these are real concerns.

BORGERSON: For sure, and there are different attitudes about how the Arctic might be developed. In fact, if you remember the headlines of the Greenpeace activists who were actually seized by Russian border patrol, the Arctic is a vast and beautiful frontier but also one that’s lacking in infrastructure. And as activity is increasing, it’s very important we put in place sort of the foundations now so that we can develop it responsibly.

YOUNG: Well, and as we said, right now the U.S. a little bit behind as far as signing treaties but also behind as far as being prepared to operate in the Arctic. Russia has the biggest presence there. It controls the northern sea route. If tensions escalate between the two countries, it could increase fees to ships wanting to access the route. Russia has the world’s only nuclear icebreakers, the U.S. a bit behind in icebreakers?

BORGERSON: For sure. So Russia has the largest fleet, and in fact even non-Arctic countries like China and South Korea are building icebreakers faster than we are. And so we’re way behind in having the capability to operate there, and the U.S. Coast Guard is in need of a budget to actually build new vessels.

There’s actually five things, I think, that the United States can do to try and increase our position in the Arctic, because next year we assume the chair of the Arctic Council, and we have an opportunity to provide some leadership there. But frankly we’ve been a laggard on Arctic issues relative to others. So first as mentioned, we need to join the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. That’s urgent, not just for the Arctic but for global issues.

Second, we need recapitalize our icebreaker fleet. The United States needs infrastructure there: ports, roads, air fields, et cetera. We need to revitalize our diplomacy in the Arctic and perhaps have an Arctic ambassador like other Arctic nations.

And lastly, and this is less specific but perhaps the most important, America needs to sort of wake up to the Arctic and needs to change its attitude about the Arctic’s new centrality to international relations.

YOUNG: This is not your grandfather’s Northwest Passage.

BORGERSON: No. In fact, in the 19th century, British and others were looking for the fabled shortcuts, and climate change has changed everything. They got blocked because of ice. The Arctic is melting at an unprecedented, unbelievable rate. Half the overall area of sea ice has disappeared in the last 30 years, and nearly three-quarters of its volume. That’s just an extraordinary number. And this rapidly disappearing sea ice is just dramatically transforming the region.

YOUNG: Scott Borgerson, former Coast Guard officer and Council on Foreign Relations fellow. He’s been called the America’s foremost expert on the Arctic. Scott, thanks so much.

BORGERSON: My pleasure, thank you.

YOUNG: And by the way, Scott’s working with the NGO Terramar, trying to protect reserved public borders in the Arctic. We’ll link you at hereandnow.org. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.